Oh, creativity. It required time, energy, and at least some level of peace, quiet, and mental space. But for the past three years I dealt with an overabundance of “you have to’s” that resulted in very little free time, energy, or quiet. In a most remarkable turn of events, at the end of a three-year marathon of obligations I was rewarded with a noteworthy and glorious gift: the first full week off at home in fifteen years, and during a national holiday no less.

In any given “normal” week I was alotted a very narrow window of time for creative pursuits after employment and family obligations were met, and a big event like a move to a new house always cut my free time to zero for weeks or months. My family and I moved five times in twelve years.

From 2010 to 2017, we moved three times to different houses around Kamakura, Japan, though moving to a new house in Japan was relatively easy for me. All I had to do was continue fulfilling my employment obligations on the Navy base and let the wife handle the planning, paperwork, packing, unpacking, and coordinating of kids. We also got significant help from family and friends.

We lived in Kamakura a total of ten years, during which time I never experienced a full week off at home. Okay, I did take paternity leave both times we had a new baby in the house, but of course those weeks could not really be considered “time off”. During the decade in Japan I did take a week or so off a few times a year, but that time always seemed to be dominated by family vacations and other events.

When time permitted I paddle-board surfed the beaches of the Shonan Coast. Whenever we moved to a new house, it reminded me of paddling against a strong offshore wind, using all my strength just to avoid getting blown out to sea. But over time the storm would pass and things would calm down enough for me to write a story or two.

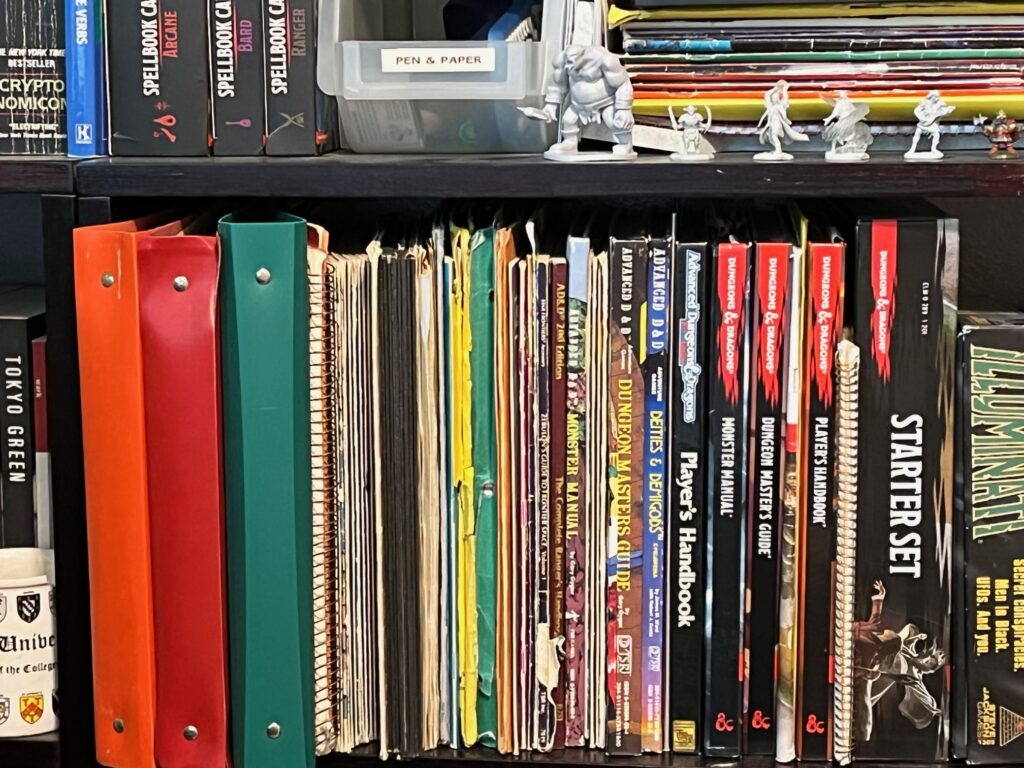

Between 2016 and 2018 I even managed to write a novel in the lull between moves, though this effort involved extreme levels of discipline, dedication, and deprivation of sleep. I established a deadline to publish Tokyo Green by 2018 because for a long time I had known what horrible life-changing endeavor came next.

Our trans-Pacific move from Japan to the United States in 2020 was quite possibly the most difficult project I had ever attempted. I arrived in Utah (of all places) two months before the rest of the family. For a long time it left me with zero creative time and a very angry muse. There was a gap of almost one year during which I didn’t write a single blog post, between the “2020 Job Search Journey” and “The Great Return”. There was so much to do, and as the only adult American in the family I had to do all of it – the paperwork, planning, unpacking, getting the kids registered in school, and what-not – just as my Japanese wife had done in Japan. Fair enough, but I was also the sole breadwinner of the family, holding down a full-time career that I did not want, enduring the puss-spewing wound of a midlife crisis that would seemingly never heal. The Great Return was a storm that blew me out to sea so far that I could not see the shore.

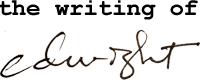

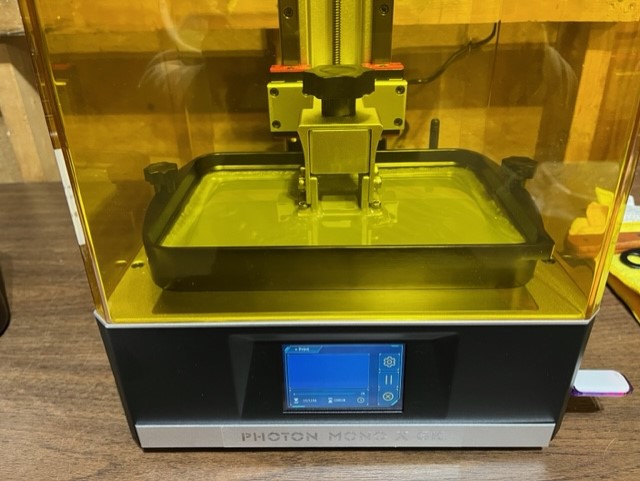

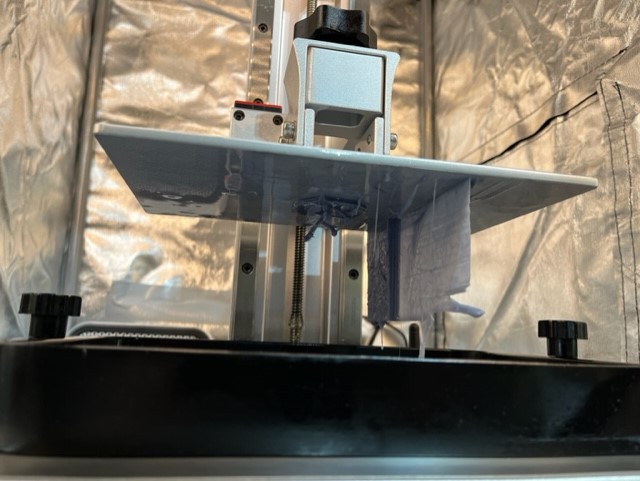

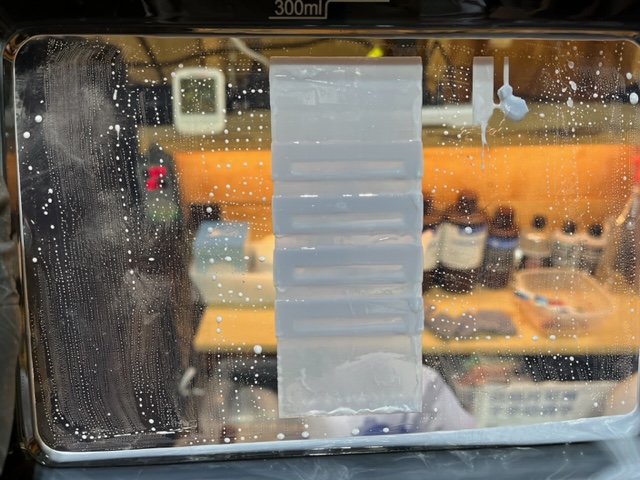

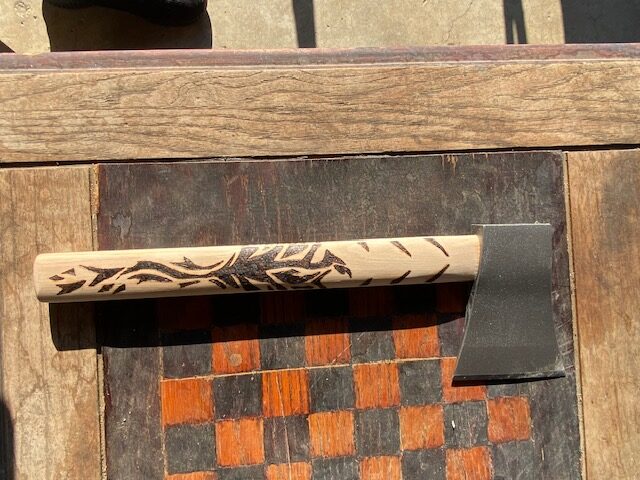

As a year or two passed I found the time to engage in creative projects like 3D printing, pyrography, painting, and playing D&D with the kids, though writing on a semi-pro basis was still the furthest thing from my mind.

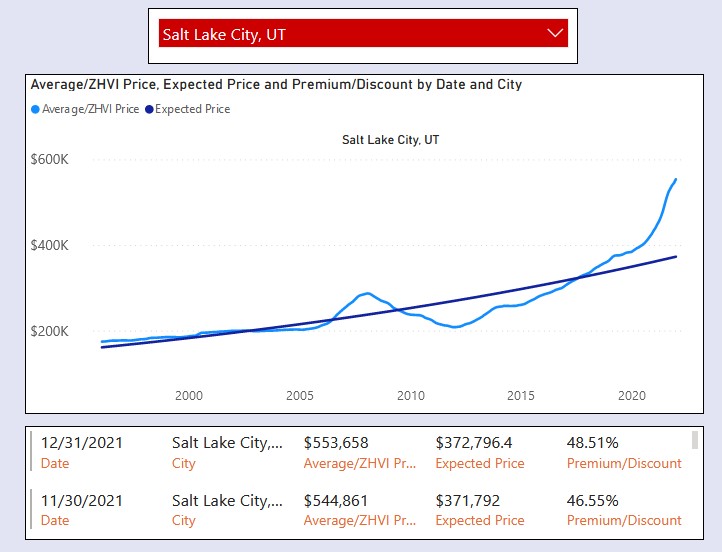

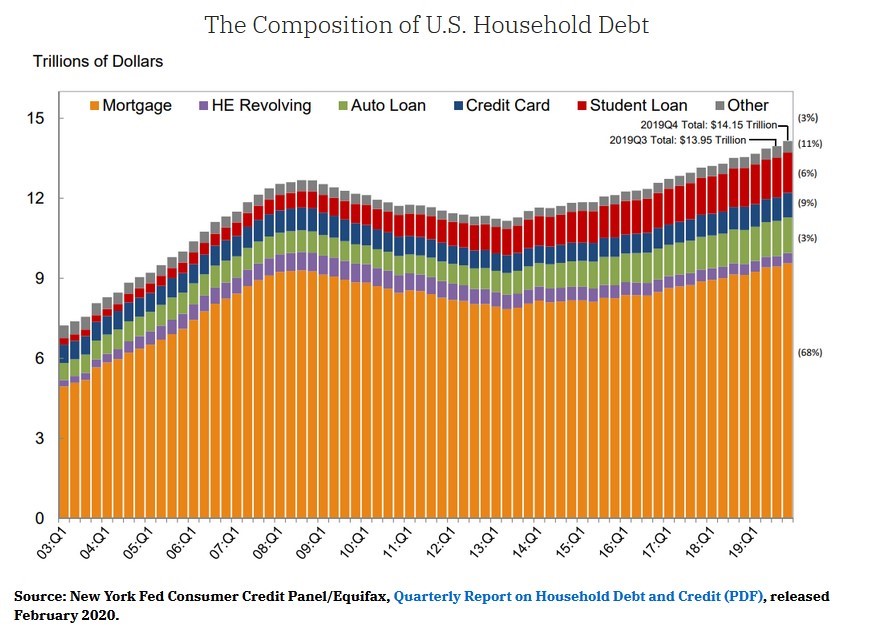

In 2023, I engaged in perhaps the second most difficult project of my life: yet another move, but this one just a couple miles away. It took comparable effort to defy America’s great, silent housing crisis and move us from our so-called temporary, low-cost housing to something more suitable for us. I took an eight-month break from writing blog posts, and my infrequent journal entries were for the most part to-do lists and gripes about not having enough time to honor the muse. My wife and I dumped an insane amount of time and energy into house-hunting. The miracle did finally happen, but once again I would tackle all moving tasks alone.

My wife and kids would be in Japan all summer. They weren’t escaping the move efforts; this trip had been planned long before we knew we’d be buying and moving into a new house. So once again, for the second time in three years, all moving tasks fell on my shoulders: the house-buying, the dreaded paperwork, the physical move itself, the unpacking, the additional furnishing, the necessary renovations, and everything else – all while holding down the involuntary obligation of a demanding career as sole breadwinner of the house. What an amazing thing my membership of the so-called American patriarchy was! According to whatever sadistic maniacs came up with this concept, I was the most fortunate and priveleged son of a bitch in the world.

For a few weeks in July of 2023 I did join the family in Japan, but for a couple of months I was alone without them in Utah. I hated our time apart, and it added additional stress. But I did get a lot done in terms of getting moved in and settled in the new house.

They returned in August and that’s when an even bigger wave of to-do lists began. For the next couple of months I was paddling with all my strength, continually solving problems around the house, and pushing back on the wife’s frantic pace of getting everything perfectly squared away in the narrowest window of time. We were going to be in this house for a long time. Did we really have to do everything right now? It got to the point where I’d flinch everytime my wife opened her mouth, because I knew she’d stack yet another task on top of all the other things I hadn’t yet found time to do.

By late November of 2023 the worst was done. The persistent paddling had paid off. We were sufficiently settled in for the holidays, and I welcomed the winter snow. By mid-December all the kids’ holiday activities (the recitals, parties, and what-not) were done. Only one set of obstacles remained: Christmas get-together’s with family and friends.

Then, I was blessed with a double whammy of good fortune. First, my brother’s dog died. The original plan had been for my brother and his family to spend the holidays in Mexico, while my mom came out and stayed at their place to watch their dog who was too old to make the trip. Pico the Chihuaua was a a legendary dog and a great hiker, but with his death my mom cancelled her Christmas visit. “Shucks! Say it ain’t so!” I exclaimed with disappointment in my voice but with relief in my heart. I would so miss having someone around to make continuous unsolicited suggestions about how to improve my life during my one precious week off.

The next stroke of luck was that my wife got sick. I had never seen her so sick. She couldn’t get out of bed for days. The holiday plan-maker and to-do list filler-upper was effectively disabled! All I had to do was work and take care of the kids. This was a welcome burden compared to all the engagements she’d no doubt be planning and all the tasks she would otherwise ask me to do. We never identified whether she had COVID, but who cared? COVID was the golden ticket to my ideal situation: solace and exemption from unwanted holiday hustle, even if it resulted in death.

So, that was how I got my first full week off at home in fifteen years, and I remained strong and healthy throughout. What did I do with this time? I skiied. I walked. I unwound. I reflected, spent time with my family. I wrote goals, and thought about how to get back on track. What was the track, anyway? Where was I going? Through all the excitement I had forgotten who I was or where I had meant for my life to go. Why had I paddled so hard and for so long? What had it gotten me? Now that the storm had passed, what would I do once I at last set foot on shore?