Almost all of Americans were in either of two groups when the Great Housing Disaster of the early 2020’s hit. For the most part, neither group realized there was a housing disaster at all. Group One consisted of the people who already owned a house, and Group Two were the people who could not afford a house to begin with.

There was also a Group Three, a very rare species of prospective first-time homeowners who were equity poor, debt-free, and cash rich – but who were still unwilling to bet their financial futures on whether this economic insanity was normal.

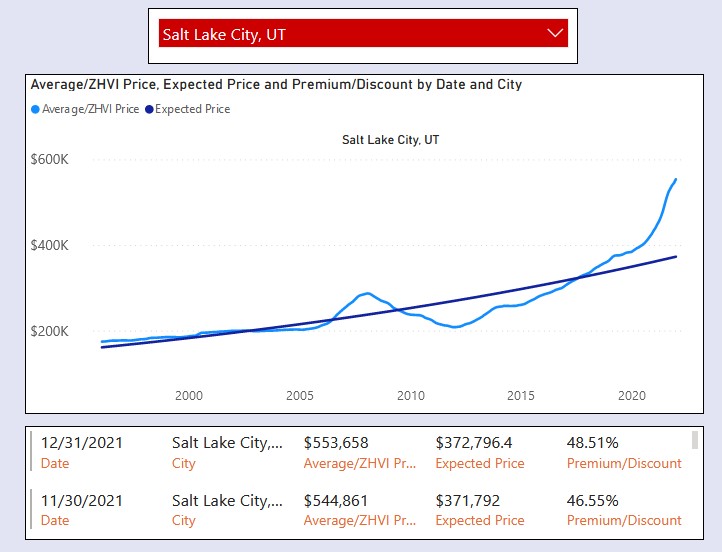

And how could it be normal? Housing in America had never been more expensive, in either real or relative terms. The median house price in America had more than doubled since the great recession, increasing fifty percent in the COVID years alone. For sure, nobody’s household income had come close to doubling during this time. Forget eight or ten percent inflation on a loaf of bread. What about one hundred percent inflation on the price of a house, the most expensive thing most people would ever buy? This unprecedented economic paradigm shift was one of the most impactful slow-moving events of the twenty-first century, but astonishingly it didn’t get much play in mainstream news.

In A Basic Necessity – Part 4, I overcame my self-pity, shock and despair over this housing disaster and its terrible timing (what were the odds this would occur at precisely the time I had planned to buy a house, after having saved for thirteen years?) and committed to buy a house that was suitable for me and my family. There was considerable negative motivation involved. Our so-called temporary housing situation was way past its expiration date and it was having a negative affect my mental health. We needed to escape our tiny duplex on the shabby, low-income street with its depressing stretch of junk-covered lawns, shirtless chain-smokers, spilled garbage, dog poop, and cars on blocks.

Every weekday morning I surveyed this street as I walked the kids to school. I was no safety freak, but there were very real safety concerns around our house. On a crime map it wasn’t quite red, but maybe orange or yellow, depending on the week. Mild safety concerns aside, I walked the kids to school every weekday morning to get some fresh air, stretch my legs, and clear my mind before the work day began. Most of these morning walks were in very frosty weather, with snow and ice everywhere, before the sun appeared over the mountains to give the valley a little warmth. We had record snowfall in 2023.

At the kids’ school I’d see them off, and then walk back up the hill to the house, reciting my goals like a mantra, the first of which was “I help elevate the lives of my family by doing great things, including (but not limited to) a major housing upgrade this year”. This goal seemed impossible, but I forced myself to repeat it through clenched teeth, every single day. This went on for most of the school year. At some point toward the end of winter we took action. The wife and I started looking at houses for sale. Out of maybe twenty houses, we saw three that we considered suitable for us.

The house search was depressing because:

- I still felt like I was nowhere, despite the mountains and outdoor lifestyle perks.

- The quality of houses in our neighborhood were not that great on average, as compared to anywhere we had ever lived.

- And houses were still selling for an insanely inflated price, as compared to just a few years before.

The same question churned through my mind for years: what was reality? The price of housing had never gone up so much and so fast. I didn’t mind paying whatever was actual value of a house, even if it was near a million dollars on average in our area, but I did mind paying that kind of money for an otherwise very average house.

Supply was still a major problem that drove prices impossibly higher. The homeowners in Group One were not selling because nobody could afford to move (and thereby double their mortgage payment).

As May rolled around we were still looking at houses, but our enthusiasm had slacked. We had recently found two houses we liked, but couldn’t get our foot in the door. One of them had an “unlimited” cash offer. It was reminiscent of the FOMO frenzy of the previous two years. My wife and kids would be in Japan for most of the summer, departing the first week of June. I was planning on joining them there for most of the month of July. We had more or less decided to suspend our housing search until autumn, but there was one more house.

I didn’t want to see it. I was too defeated, depressed. My wife talked me into it. She loved this house. The place was fifty years old, but very well upgraded and maintained. It checked off all the boxes for us, and other boxes we hadn’t imagined. If rented, this place would go for at least $3,500 per month. If we took out a mortgage, we would’ve paid hundreds of thousands in interest over the full term of the loan. In my mind there was no way we’d get this house.

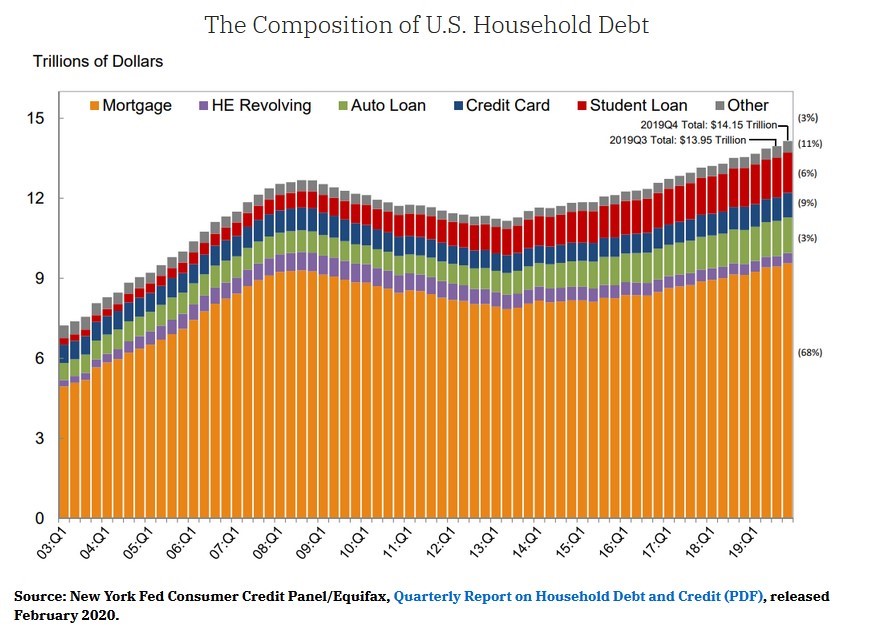

But we did. We were fortunate to be in Group Three. Ours was not the highest offer, but it was cash. Being cash buyers was like traversing this economic hellscape with a special immunity card or an amulet of protection. Credit scores and interest rates were irrelevant. We had lived a frugal life for decades, never accumulating a single penny of debt.

So we succeeded. All those months of reciting my goal through clenched teeth in frigid weather had finally paid off. Three years after having made the move from Japan to America, we were finally “home”.

Our problem might have been resolved; HOWEVER, one thing had bothered me during this whole endeavor: how would our children and future generations ever be able to buy a house? Was this a permanent paradigm shift that signaled the end of traditional quality of life in America? My family and I were fortunate to have had financial liquidity and leverage that were unheard of for most people, and it still seemed miraculous that even we were able to overcome this economic disaster. Would future generations become permanent renters, with a small minority of landlords and investors rising to the top? Was the single-family home a thing of the past?