This January I engaged in a couple of projects that absorbed all of my spare time, forcing me to put my usual creative activities on hold. First there were the holidays, which was always a project unto itself, with all the obligatory get-togethers, visits from extended family, and gift coordination for the kids. A couple weeks before the holidays my wife had instructed me to build a personal computer (code name “Slacker”) for our oldest boy. I put it off until January, knowing what an effort it would be. I was also informed that I’d be waking up in the pre-dawn hours every Friday morning in January to take our youngest boy to skiing lessons at Brighton, up Big Cottonwood Canyon.

For the most part, my life was directed by a meticulously-organized Japanese woman, and I was okay with that. However, January was the month that I had planned to dive feet first into the training that would help me evolve my career and thereby allow me to elevate the lives of my family (in the form of a major housing upgrade in 2023, for example), and of course there were my usual creative projects, prerequisites to positive mental health. In the triad of goal categories I had created (family / creativity / vocation), family came first. I’d have to put creativity and vocation on on hold for a while to get these family projects done.

Four mornings at Brighton ski resort might not have seemed like too heavy of a chore, and in fact it may have sounded downright luxurious; but Friday mornings were normally my slot for prime-time productivity when it came to advancing my conditions at work, and for exploring whatever creative projects I had going at the time.

Very close to every hour of my remaining free time in January was devoted to the great PC upgrade. In truth there were two upgrades: upgrade number one was my son’s first PC, which I’d build using some of the components (motherboard, CPU, power supply) from my current gaming rig, Slacker, and install them in a new PC case with new RAM and video. The motherboard, CPU and RAM were about seven years old, but with the new video card they’d suffice. I’d also involve my son in every step of the hardware assembly and wiring, making sure he understood how all the parts fit together and how the system worked. Upgrade number two was the replacement of my gaming rig, which I’d build from scratch with all new parts. It would be nice to have a new PC, but I knew how much work it would take.

I had first started building PC’s in the 90’s, when I worked at a major electronics retailer as a techie dweeb who built, repaired, and-or upgraded thousands of computers. In the twenty years since then I had also assembled a couple dozen PC’s for myself, family, and friends. Seven years had passed since my last upgrade, and that had been more of an emergency repair, when the motherboard and CPU were upgraded to support a new video card that replaced one that had died. The technology had changed a lot since then.

The first phase of the project involved shopping and research. I took notes. LOTS of notes. For example, if I wanted X hardware feature on one component, would the other components be compatible? Was X component worth the extra X dollars it would cost? Would there be any noticeable performance increase? Would it be upgradeable in the future? For these evaluations I leaned heavily on my Canadian geek friend in Ontario. We had worked together for many years, and he had remained more tech-savvy when it came to assembling PC’s. We established a price-to-performance matrix with various upgrade paths and options. I spent maybe eight hours over the course of a week in this phase of the project and then sat back and waited for the waves of deliveries to arrive at our door.

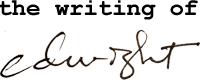

The next phase of the project involved a) the disassembly of Slacker, my current gaming rig, b) the assembly of my son’s computer with old and new parts, and c) the instruction that went along with it. I set up an informal curriculum that involved explaining the function of each component and how they all fit together. We spent a couple nights after dinner putting things together and talking about how computers worked, and even more time on troubleshooting and configuration. This phase took maybe ten hours total. (Instruction on internet safety would come later!)

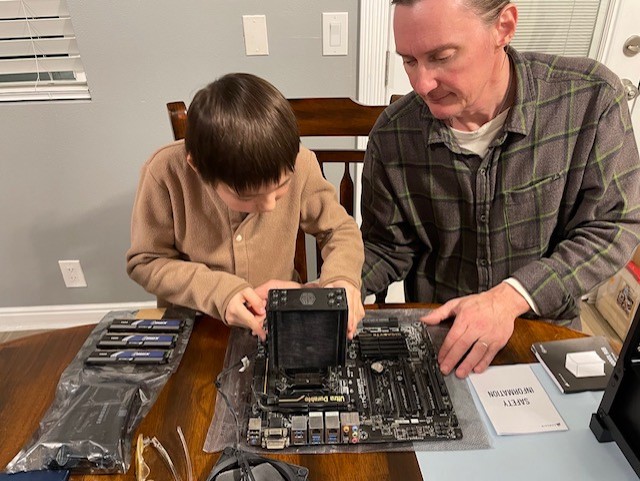

The technology may have advanced, but PC upgrades were basically the same. My hands were always too big to fit into the spaces they needed to go (so my son’s half-size hands came in handy). There was always a screw that got dropped into the chassis, never to be seen again. It was rare that any part fit perfectly. There were always bloody injuries, like when I first took the PC case out of the box and removed the tempered glass front panel, only to have it slip out of my hands, hit the hard floor, shatter, and slice my thumb open in the process. (Ironically the paper I grabbed to stop the blood flow was a manual of Safety Information.) Cuts on the tip of the thumb were a real joy because it was almost impossible to avoid jamming the wound into something every few minutes, especially when building a PC.

And once we finished assembling my son’s PC it had to go somewhere. Our house was small and there was only one place it could go. This required rearranging furniture and getting a desk ready in our dining room. All the stuff that had been on the desk had to go somewhere, too, so we got a cabinet from IKEA and I spent a Saturday afternoon assembling it with our youngest son. This was a enjoyable family endeavor, I had to admit.

After a couple weeks the first PC was up and running, and the parts for the second PC had arrived. It was time to do it all again, this time from scratch. Most of the hardware assembly I got done in one night. Organizing the cabling inside the case was another full night. It was a geeky art form, the closest task that resembled creativity in this type of work. I liked things in the case to be attractive and neat.

The final step of the hardware install were three NVMe solid state drives. This should have taken three minutes. It ended up taking over three hours. The modules came with built-in heat sinks that made them slightly too big to fit in the M3 slots on the motherboard. The screws that were supposed to secure the modules were tiny (the size of screws that hold glasses frames together), proprietary (so a phillips screwdriver didn’t quite work), and they were too short. By one in the morning on a Wednesday night I had finally rigged something that would hold these storage modules in place (maybe), and by that time I was done, done, done with the whole project. There was still the OS and apps installs to go, along with the inevitable follow-up troubleshooting.

By the end of the month I had officially crossed the finish line of family tasks. The early morning ski lessons were done. I had successfully built two PC’s. As much of a drag some of the project had been, it sure was nice to cold-boot to Windows in 2.5 seconds, and there were so many newer games I could play with the new video upgrade. My son was delighted with his new PC, too. I was relieved to move these projects into the “done” column. But I hadn’t merely gotten these projects out of the way. I had made a permanent, positive impact on the lives of my family, and I was grateful for the opportunity to help.